Light At The End Of The Tunnel

As 2019 draws to a close, we bring you our most heart-warming story of the year. Hopefully it will be a harbinger of a kinder world in 2020.

Raising funds is not only about raising the bottom line. In some cases, it can be about upping the ante on kindness.

Cutting through bureaucracy and providing financial support, Compassion Fund is a crisis response fund supporting needy students from low-income families facing a recent death, an illness or accident of a family member, resulting in loss of income. And leading this philanthropic organisation is Chairperson Mrs Kay Iswaran, who has been at the forefront raising funds to ensure that many needy families get monetary assistance.

A recent fashion show-cum-charity event, Gala of Light, managed to raise $520,000, which was equally shared between Compassion Fund and Beyond Social Services. It was the first time a fashion event organised by non-resident Indians (NRIs) had collaborated with a local charity. Mrs Iswaran was introduced to the organisers Bina Rampuria and Samia Khan of Melange by a common friend, who was looking to do a gala event to support local charities.

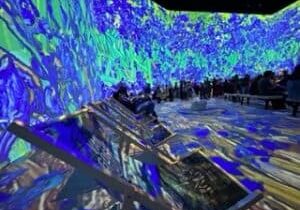

Although it was held during the Deepavali festival season, the inclusive name Gala of Light was suggested by her husband, Minister S Iswaran, Singapore’s popular minister for Communications and Information. This event was also jointly sponsored by Eurokars Group and Lum Ching Builders, supported by Porsche. It was a spectacular evening with a cocktail reception, seated dinner, fashion show by well-known Indian designer Anita Dongre, live auction and after party entertainment. The event marked the Indian festival of lights – Deepavali – a time for celebration, gratitude and giving.

“It was a wonderful thing and a very good idea to reach out to the Indian population,” says Mrs Iswaran. But what differentiated this event to others was that although it was a Deepavali event, the sponsors were all top Singapore corporations and the well-heeled participants were an equal mix of Singaporean Chinese and other expats as well, all dressed up in Indian attire and having a great time. “That was what we were really going for. I would be really interested in knowing the breakdown of locals and foreigners and I wouldn’t be surprised if it was 50:50,” she said in an exclusive interview with India Se Media.

Mrs Iswaran, whose second child out of her three children has Down’s Syndrome, is a natural standard-bearer of a charity like the Compassion Fund which she has been heading for the past few years.

As she talks about her three children her gentle green eyes light up with love and pride further leavened by a dose of stoic humour, that hints, touchingly, at a coping mechanism in bringing up a severely disabled child.

Talking about her pet project, she stresses that it is completely private and while the money is for students, it is given directly, and almost immediately, to the stricken families to ensure that affected households can keep their students in school and reduce the stress associated with it.

The fund, which has a budget of $1 million, is the first physical support that poor families get when struck with a sudden calamity. The cash payment supports families that have lost their primary source of income either due to death, accident or major illness. Since Compassion Fund is a child-centric charity, the family must have child dependents to qualify and a pre-crisis per capita income of not more than $650.

“However, families could face a double whammy if one person has cancer and stops work and the other person, being the principle caregiver, too may not be able to continue,’ says Mrs Iswaran who takes care to explain the complexity of assessing a family’s need and how crucial this micro-comfort is in the first few hours of the family’s bereavement.

“Any family losing their income can be very difficult, but if you are a poor family just making your ends meet and suddenly there is no income, people don’t have the safety net of a job that will pay them six or 12 months,” she explains. On the upper limit, Compassion Fund provides as much as $350 PCI.

“We have a more holistic approach and our own guidelines on helping needy families.” There could be many reasons people may not be able to get help from the government and that’s when Compassion Fund steps in. “Sometimes we may only help a family for a few months after which they may get a pay out or government help. We aim to be very fast and step in early,” she adds, as she delves into the day-to-day workings of her fund – something that is clearly a passion for this self-deprecating mother of three children, one of whom is still in school.

Cutting across red tape, a case worker usually visits a needy household to assess the situation first-hand. “Once, the family is able to provide us with all the necessary information, and we can see at least one family member, we approve support very swiftly,” says Mrs Iswaran.

Once the pay-out is approved, reviews are conducted at the end of three, six and 12 months. Usually financial assistance is provided for one year, but if a family is unable to solve its problems, then they are supported through another fund called Silver Lining. Currently, Compassion Fund supports 113 families currently, but at any given point of time, it is financially assisting and building a network of support for approximately 120 Singaporean families in tragic circumstances.

Talking about the difference between Singapore and other welfare states where the government provides regular hand-outs with many depending purely on the dole, she said, “I have lived in Australia, but I like it (here), because there is not this relying on charity. There are some negatives in that (reliance on charity). People get used to the doles and pay-outs. The government here, in a lot of their policies, serve the fabric of society. It has a social net and they encourage charities in filling the gaps. They come through a system.”

Families are also aware that this support will not be forever and therefore constant encouragement and guidance is provided to ensure that they can be self-sufficient. However, in cases where there is some need and if the family has used up the Straits Times Pocket Money Fund, the family may qualify for its Student Assistance Fund, that is about $50.

“We often have this discussion that we are helping out, but not quite enough. Sometimes you look at all that goes wrong in a family, then you think that the money is not quite enough. That’s why we look at it in a holistic way. Hence, we are not over giving, in fact, we are under giving,” says Mrs Iswaran.

The tall and pretty brunette who settled in Singapore after her marriage more than two decades years ago has obviously melded well and sees herself as a Singaporean more than anything. Not surprising for someone who has spent more than half her life in the home of her Singaporean husband whom she met as a very young girl. They were both students in the University of Adelaide. “I was 18 and he was 19. I came here because of him,” she lets on with a disarming blush.

In her first few years in Singapore, Mrs Iswaran – a science and arts graduate – taught for two years at Anglo-Chinese Junior College. Along the way, she also studied psychology. Although Singapore was a big change from small town Australia the young bride adjusted well to her new Tamil family and soon made herself at home, even picking up enough Tamil to communicate with her mother-in-law. Two of her children, the oldest and the youngest – Monisha (22) and Krishnan (16) – studied their mother tongue at school. Her middle son, Sanjaya (20) is a special needs child with Down’s Syndrome who attends an adult day activity centre. It is obvious that as Sanjaya’s main caregiver Mrs Iswaran’s world view and humanity has been honed to a fine degree, making her a perfect fit for her role as head of the Compassion Fund.

It is writ large in her day to day dealings with her “clients”. Recalling an inspiring experience, she narrates with a catch in her throat her awe in interacting with a remarkable single mother and her daughter who had Down’s Syndrome. “This is a family where the father had died and the mother too had a problem with her legs and mobility. Their daughter, who is the same age as my son, had Down’s Syndrome. The mother could not work long hours and was afraid to leave her daughter unattended. This is one of the cases, where technically there is an able-bodied person, who also needs financial assistance.”

Although the mother had rented out a room, the income was not sufficient to make ends meet. So apart from financial assistance, Compassion Fund social workers are also trying to help the daughter find a job after finishing at MINDS (Movement for the Intellectually Disabled of Singapore). “The young girl is amazing, quite independent, and almost as old as my son. We are hoping to find her a job. Though there might not be much money, but even a little bit can make a big difference to them,” says Mrs Iswaran.

What she leaves movingly unsaid speaks louder than words: It is such small victories that spur on the tiny team at Compassion Fund.

VOLUNTEER CASE STUDIES

Mahesan Kurukal, s/o Ramanatha Kurukal (29) is a caseworker at Compassion Fund. The young man opted to work in the social service sector, as he believed that this gave him more satisfaction than working in the corporate sector. He is simultaneously pursuing a degree and has had prior experience having worked at a nursing home, destitute home and elder day care centres. He also did a stint at the MCCYS and finally found his true calling at Compassion Fund. “Had I not got this job, I would have joined the army,” he said.

One of the cases that touched him the most was that of a Malay family. Mahesan could relate to them because just like his own mother who had been diagnosed with leukemia, the father of the Malay family had also suffered and eventually succumbed to cancer. The widow’s two older step-children too started making claims from their father’s pay-out and she had four young children of her own who needed to be educated. This was a difficult case and it took over one-and-a-half years to settle things as we had to use all the community resources available to us,” he said. Since then, though financial assistance has stopped, the woman has been on the road to recovery and her four children have continued their education.

Nerosha, d/o Ravindaram is a 29-year-old case worker at Compassion Fund. She is its newest employee and has a degree in counselling. Prior to joining the Compassion Fund she worked at AWARE where she ran a helpline and trained other volunteers. She was also part of the team that started the Sexual Assault Centre at AWARE.

Nerosha was also touched by the mother-daughter case (mentioned by Mrs Iswaran). She understood how financially deprived the family was when the mother told her they had to wait till the end of the month to eat some biryani or a burger at McDonald’s. “These are things we take for granted and that led me to think what else I could do for the family. I wanted the girl to get gainfully employed and so I went to the Down’s syndrome Association to see what more they could do to get her some work. The extra money will go a long way.”