‘Each morn a thousand roses brings, you say; Yes, but where leaves the Rose of Yesterday?’— this verse by Edward Fitzgerald resonates strongly with the air of yester-year that wafts through the alleyways of the low-rise HDB blocks of the quaint neighbourhood of Alexandra Village. With the poor retail scene casting a pall over glitzy malls here, Singapore’s reputation as a sophisticated ‘shopper’s paradise’ may have suffered a blow but all is not lost. Tucked away quietly in the soporific lanes of Alexandra Village, shoppers can still find a paradise — frayed at the edges perhaps but possessing a rare charm redolent with nostalgia and history.

The neighbourhood looks like a page out of a picture book of early 1970s Singapore, with its small kampong-era shops and businesses that are almost extinct in super-modern Singapore. Familiar scenes from one’s childhood appear frozen in time, enfolding nostalgic visitors in a wistful embrace. Mama shops, frame-makers, bird-sellers, antique shops, kueh makers and juice vendors of yore dot the landscape stretching across row upon row of low-rise, character-stained old blocks housing fading trades and fortunes. They stand stoicly cheek-by-jowl with thrusting new stores selling stylish frocks, spectacles, beauty treatments and instant academic nirvana.

Quaint neighbourhoods like this one in Bukit Merah are among the few reminders of an older, gentler Singapore, most of which has fallen before the relentless march of progress but which are an intrinsic part of its heritage.

It is in these little bakeries, kueh shops, hair salons, furniture repair shops and frame making shops run by octogenarians and septugenarians that Singapore’s kampong spirit of “gotong royong” lives on. Once when a beautifully flowering tree was suddenly chopped off, a chagrined tenant wrote a complaint and collected 16 signatures from old-timers in two days before an explanation from the town council mollified her.

It is in these little shops still laced with a communal inclusiveness by avuncular proprietors that the soul of the real Singapore survives.

Sounds like a perfect Hipster paradise and there is certainly potential for that,but there’s a drawback. Old businesses in such areas are at risk of losing out to ultra-modern businesses. And it’s not just businesses that lose out. As malls offering cookie-cutter services and mass-produced items continue to carpet bomb heartland markets, old time trades and crafts disappear and with them all traces of the heart and spirit of Singapore. All that will remain will be memories.

Before they become mere archival content, India Se magazine is exploring the beauty of these old neighbourhoods to capture their essence for posterity in a series called Singapore’s Kampung Spirit. We begin in this our 10th anniversary issue with an in-depth tour of the Alexandra Village neighbourhood where our office is located and speak to some of the store owners, many of whom have been our neighbours for a decade

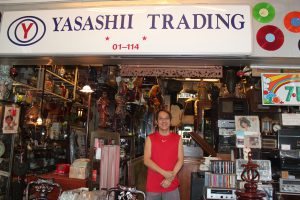

Alan, Yasashii Trading

It’s hard to walk by Alan’s shop without stopping to take a second glance. Instantly, one’s eyes are diverted to a life-like rocking horse or an imposing jade statue of a Chinese emperor. From a Qing-dynasty bed frame to typewriters from the ‘30s, ‘40s and ‘50s, his collection of antiques is so diverse and plentiful it stands halfway between a junk shop and an Alladin’s cave. His collection is worthy of being in a museum — and some items are priced almost as much. From a rag-tag collection of old furniture and junk, India Se has seen it grow into a sought-after antique shop with dealers and discerning home-makers thronging its narrow 5-foot way.

Alan Wong, whose shop Yasashii Trading is right below the India Se office, is a familiar figure to all who have been part of the India Se team and there is almost no office staff who hasn’t found a treasure there to take home. As if in memory of the business he got from India Se when both were young start-ups, he recently gifted us two ceramic elephant statues to stand guard at the entrance. “To make sure only good luck enters,” he quipped.

But how did it all start?

Alan, 51, who used to be a basketball coach at the Japanese International School began as a used furniture dealer almost a decade ago, in 2007 after he saw a high demand for it from the influx of foreign workers. When the government passed regulations that made it harder to hire foreign workers, Alan shifted his focus to retro furniture and from there, slowly began to deal in antiques.

Many of the antiques in his shop are from China. Interestingly, several of these are not available even in China. “Many items got destroyed in China during the Cultural Revolution, which lasted ten years from 1967-1976. The items that we have here were brought by the Chinese before the Cultural Revolution and are very rare in China itself,” Alan explained. “That’s why a lot of Chinese who come to Singapore want to buy back all these things, because they themselves don’t have them,” he added. Not surprisingly, antique dealers can be seen frequently rubbing shoulders with home-makers and office goers who flock to the village for its well-known eateries.

But it is a trade that is dying out, said Alan whose customer base is mostly Baby Boomers and the X generation, people between 40 and 70 years old. “I think the younger generation may not be so interested in all these antique and vintage things. Because they didn’t go through this period, he added ruefully. “In fact, elderly people come to my shop to sell their antique items to me because they feel their children may not appreciate it. For antiques you have to study a lot of history. The typewriter has its own history. The teapot has its own history. Even furniture has its own history. Every antique has its own history.”.

Mr and Mrs Chen, Rattan Furniture Store Owner

Most days Mr and Mrs Chen (that is how they prefer to be known) open their doors at 10am but much before that they can be found at the back of their rattan furniture shop intently weaving from strands of cane elegant chairs, stools, benches and other exquisite pieces of furniture The store owners both in their late 60s, whose business dates back to the 1970s, don’t import a single item. Everything is made by hand by the husband and wife and one rattan chair can take up to four days to make.

Previously located in Anson road near the port during the 1970s, European sailors used to flock to Mr Chen’s shop to buy rattan furniture for their ship decks and gardens back home. Although he eventually got involved in his father’s business at the age of 22, Mr Chen wasn’t always keen on it. “I left school and took over my father’s business. I wanted to study more, but couldn’t,” said Mr Chen, 69, who added that he would have liked to study a language. “Before I didn’t like this business, but I just helped my father because he was old. Children must help the father’s business,” he stressed, revealing a stark contrast in mindset from today’s generation, who eschew filial piety for the attractions of more conventional jobs in air-conditioned high-rises.

According to Mr Chen, he and his wife are one of the few rattan furniture makers left in Singapore, among the handful who make their furniture by hand from scratch. The others have either retired or died. As people like the Chens retire, one more facet of Singapore’s heritage will be lost. When asked if he thought his children would take over the business just as he unquestioningly did, he laughs, “No, they don’t like. Because this is a handicraft and it takes much time.”

Abdul Musa, Rahman Framemakers

As we enter Abdul Musa’s shop, we are greeted by the earthy scent of wood and an upbeat 1960s MG Ramachandran song playing in the background. Frames of all colours and sizes are methodically arranged along the walls and on the sprawling workspace table, with various measuring tools for company.

The soft-spoken 56-year old owner of Rahman Framemakers gladly agrees to share more about his business. “This is my family business, started by my father. We have been here for 35 years. Before this we were in Tanjong Pagar for six years, and then in Havelock road for around ten years,” he says.

Readymade frames, which are found in more edgy, contemporary furniture outlets now pose a competition to custom, handmade frames like his, he explains. “In ours, the wood is original wood. In the readymade, most of it is compressed wood. It won’t last beyond 3-4 years. But the frames here will last longer. And here we can make custom size, which you cannot get with readymade frames. Whatever size they come in, you need to buy. Here, we can make frames of whichever size you want,” he explains. Given that he deals so personally and closely with his customers, he emphasised that discipline, honesty, punctuality and patience are paramount. “Even if customers are angry, you must control your own anger. Many different types of customers come, we are the ones who must adjust and serve them,” he said.

Abdul Musa got involved in his father’s business at the age of 18. When asked if he had ever wished to join another profession, he instantly says no. “As a child, I was around my dad a lot, so I just decided to help him.” Frame-making is no easy work; it requires a lot of skill and long hours. Abdul Musa puts in 10 hours a day, single-handedly running his shop. He believes these long, demanding hours deter younger people from learning the trade, adding that it is unlikely that any of his three children, of whom one is a banker and one a nurse, will join the business. “It is also hard to find workers to help because many don’t have the skill or are not willing to work such long hours. While foreign workers may be willing to do this, it has become much more expensive to hire them today,” he adds..

When asked about the future of his business, which is more than 50 years old, he says wistfully, “This kind of trade won’t be there as time passes. Even now, many shops have closed.”

Jenny, Seasonal Mart

Florist Jenny Tan’s petite frame belies her big personality and the steady stream of customers is testament to her status as the neighbourhood favourite’s aunty figure. The plants and flowers she sells are an excuse for her regulars to drop by for a friendly chat and Jenny gladly indulges them, as she did with us when we visited her shop for an interview.

While camera shy, she pattered animatedly around her modest but neat shop pointing out the prized possessions she wanted me to shoot. Upon noticing our reporter eyeing a potted orchid, she enthusiastically proceeded to school us in plant hybridisation with the analogy of inter-racial marriage. “This orchid not married! Chinese marry Chinese, is still called Chinese. Malay marry Malay, still called Malay. But if Malay marry Chinese, then is hybrid already. The one you holding is hybrid, hybrid, hybrid already!” she exclaimed with squeals of laughter.

Jenny who is in her 60s, co-owns her flower shop, Seasonal Mart, with her brother-in-law Mr Chua. The shop has remained in the same location in Bukit Merah ever since it was started by her father in 1982. Showing us photos of her handmade bouquets on Facebook, she says, “Everyday morning, I do this type of flowers, which look very beautiful. Valentine’s day a lot people come. Mothers’ day also!” Jenny goes way back with many of her customers, some of whom have been loyal to her for three decades. “I know my customer a long time lah! Last time I sell bonsai, they buy bonsai. I sell cactus, he buy cactus. I sell eggplant, he also buy the eggplant!” she laughs, adding, “Last time I do flowers for his car during his marriage. Now I’m doing it for his son’s marriage!” Jenny’s loyal customers keep coming back due to her personalised services. Back in her heydays, she used to go the extra mile by tying intricate floral arrangements onto the cars of newly-weds — something seldom seen today. It is obvious that over time Jenny has created a warm, friendly bond with them. When an elderly lady comes to the shop looking for flowers, she sends her away, saying “Don’t buy aunty! Too expensive!” When asked why she did that, she explains, “That’s my regular customer. I know she always wants only the $7 flowers, that one we don’t have today. I know my customer’s patterns and they also know my pattern, so I can talk to them like this. They won’t get angry!” she chirped. Such frankness would be offensive in an upscale mall but for her customers it’s a sign of Jenny’s caring nature.

However, getting by is not easy for Jenny, who slogs ten hours a day. When asked how she does it even at her age, she says she has no choice. “The rent is very high. If you want to pay the rent, you must open. Not easy, I tell you. Must make at least $6000 a month. $4000 give government to pay rent. Then another $2000, must pay for the water, the electricity, all that. Then makan eh?”

Despite the struggle, Jenny values her principles above possessions. She trusts her customers and allows them a free hand in her shop. “Cannot jalan here, jalan there, [Malay for ‘go here, go there’] must leave the customers to see. If they want to curi [Malay for ‘steal’] then I just let them. Because you come to the earth, you bring nothing. Afterwards when you go from here, you also got nothing to take. If people still want to curi, then aiyah, nevermind, give you to curi.”

As we take her leave, she springs a surprise on us.

“Aiyah I give you, lah, this one! Nevermind, I give you!” she exclaims, thrusting into our hands the potted orchid our reporter had been interested in earlier, refusing a single cent in return.

We are too moved to protest much but as we leave we offer her a quick hug and a silent prayer that her flower shop never shuts down.