Just. Imagine

Last year, amid growing child poverty, a severe water crisis and outbreaks of violence in our country, a well-meaning journalist, Ansar Abbasi, raised a most urgent concern, causing people to panic and protest against a private school in Karachi. The cause for concern here was none other than John Lennon’s 1971 song, Imagine, which the school had decided to include in its concert for children to sing as a message of hope. “A private school in Karachi is holding a concert on Friday. Students will sing John Lennon’s lyrics- no heavan [sic], no hell, no religion too,” he tweeted. He called upon the Sindh government to intervene. According to Abbasi, singing this song would tarnish their character, jeopardise the morals of our new generation and expose them to the vile poisons of secularism.

Confusing secularism with atheism, Mr Abbasi panicked on Twitter to his 517,000 followers that Pakistan was in danger of being secularised — the very thing that Mr Jinnah had imagined the nation to be. Or was secularism something he had warned us about? It seems that the state narrative has distorted our nation’s history so much that one can no longer be sure what Mr Jinnah said or didn’t. For our forward-thinking, progressive, ‘Western-educated’ leader has been reinvented as a traditionalist and a separatist who despised the Other. And so, in keeping with that rhetoric, the assumption is that we must too.

And what is this Other? It is no longer just otherness of religion or sect but the otherness of the so-called ‘liberals’ who are perhaps the fastest-shrinking minority and the most threatened of all species in the land. It is these annoyingly tolerant, secular, peace-loving, moderates who have come to represent the stranger at home, the odd ones out, the foreigners in their own land, for their message of tolerance and of live-and-let-live is mistaken as ‘slavery to western thought’ among the do-or-die believers — as if Islam preached no such ideals of peace and equality.

And here I must mention that the institution in question is older than the country itself with a rich and vibrant history of producing some of Pakistan’s best leaders, athletes, business people, academics, actors, journalists, doctors and other professionals. Most parents go to great lengths to send their children to this school for it has come to represent a symbol of academic excellence and prosperity, and one that guarantees to open the right doors of higher education and a professional life for their child.

An apt analogy here would be with those people whose faith in Pakistan is so shaky (“Is mulk ka kia bharosa?”) and who despise the US but then run off to America to have their babies to secure foreign citizenship. They are blissfully oblivious to the duplicity of manner in which they hanker after prestigious schools and colleges like the one in question but once their child is enrolled, question the very morals and values that made that institution great in the first place. One is reminded of terrorists who, on the grounds of ideological and cultural non-compatibility, attack the very land that raised them, be it Pakistan, Afghanistan or France.

But what all these people forget is that these places of learning would not be so esteemed had they not enshrined those very values these people deride. How have these institutions (or countries for that matter) become sought after? Is it just because the children of the rich and famous go there? These institutions have gained their formidable reputations because they have a vision and that is to produce thinking, questioning critical citizens. Of course, thanks to the efforts of right-wingers like Mr Abbasi, they don’t always succeed.

Institutions such as Karachi Grammar School, the Institute of Business Administration, the Lahore University of Management Sciences, the National College of Arts or the still young Habib University, which are making a name for themselves regionally if not globally for providing a quality all-rounder wholesome education, are known to promote liberal values. In fact, the biggest challenge these institutions face is not getting students to learn but to make them unlearn. They are taught to look beyond the obvious, to understand context and subtext, in short, to think. And what is more threatening than a person who can think for themselves?

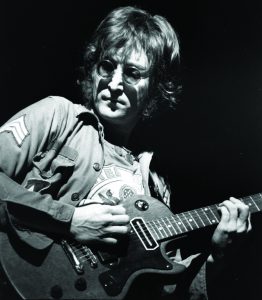

In keeping with the message of thoughtful self-cultivation, the school had chosen John Lennon’s song in the hope of promoting peace, tolerance and respect for everyone in the world. Is this not an excellent choice given what is happening in our country, the bomb blasts in neighbouring Afghanistan, the killings in the name of convicted rapist Gurmeet Ram Rahim in India, not to mention the White Supremacist marches in Charlottesville? The song, whose lyrics wish for a world where people are not divided by their race or religion and where there is no war, is a utopian hope for a harmonic realm. However, despite all this, Mr Abbasi interpreted the song very literally and became afraid that it demanded we erase our much loved border with India, not to mention do away with the fear of Hell. What then would we scare our fellow countrymen with? No fear of God and worse no fear of India? He belted out a tweet, causing mass panic, anxiety and using his social media influence as irresponsibly as possible, incited many to threaten the school with accusations of blasphemy. Even more distressing was that the school, left with no choice given rigid and unyielding laws around the question of faith, was forced to change the word ‘religion’ to ‘hardship’.

Mr Abbasi did not, as one parent said, bother to think he was putting at risk the lives of 200 children. Have we forgotten the children of APS Peshawar so easily? Are all children’s safety not our concern? (Several people asked him to reveal the name of the school on Twitter and one television channel went right ahead and named the school). What of the young schoolgirls in Nigeria abducted by Boko Haram for attaining a ‘western education’? Who cultivated that mindset? Where did this narrow self-righteous thinking germinate? It too must have begun with a conversation, with a speculation. It, too, must have been a point of view that became so cemented and singular in one’s mind that it led to a radical and violent condemnation of all Western education as evil and immoral. Mr Abbasi, too, in a similar fashion, went on to remark on national television that the real problem was the school being run by an Englishman, accusing the students and their parents of being slaves to Western thought.

His words are strangely reminiscent of Boko Haram’s ideology. Perhaps they both belong to the same school of thought. And in this narrow and literal world view there is certainly no room for Mr Lennon’s ‘living in peace’. There is no room for thought, let alone imagination. This is a world where people are lynched for their beliefs, where women are murdered in the name of honour, where universities breed extremism. And as a parent and as a teacher, I worry for our new generation of Pakistanis who will have to inherit this old one with their narrow, shrinking world views that are so out of synch in a world that is becoming more and more global. The gaps are closing in and this is the time to make a choice — to stay silent or to push back against this narrow-minded bigotry, which we have already put up with during many a military rule. It is time to imagine a better world, one where binaries of faith don’t dictate basic human emotions of apathy and compassion. We are bigger than this. And I hope that when push comes to shove many of us will choose to sing Lennon’s song than this old tune that we have been dancing to for far too long.